This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

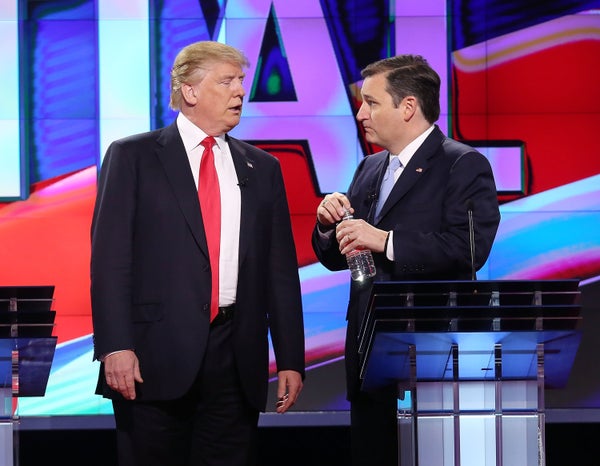

Almost everyone bemoans the attacks and finger pointing that have become an inevitable part of virtually every political campaign. Candidates who agree on little else claim to share this frustration. Bernie Sanders has emphasized that he’s “never run a negative ad in his life,” and Ted Cruz has lamented debates designed to create a “cage match” atmosphere.

So why do so many elections nowadays, including the current presidential race, ooze with negativity?

Researchers say that cultural trends and human psychology may help explain why such attacks infect campaigns with the persistence of a foot fungus. But they have some welcome news as well: Tweaking the voting system could help treat the chronic hostility.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

First, the bad news: Cultural shifts may have set the stage to make negative campaigns the rule rather than the exception.

On its face, this might seem surprising. Research suggests that voters have grown increasingly reluctant to identify with a political party. According to a paper in the March issue of the journal Electoral Studies, only 63 percent of voters identify as Republicans or Democrats, the lowest number since 1952, when the American National Election Studies survey began.

Despite record low identification with political parties, however voters split along party lines more than ever. Americans are more likely to cast votes for the same party down an entire ballot than at any other time since World War II.

“Among people who call themselves independents, the vast majority are what I call ‘closet partisans,’” says Alan Abramowitz of Emory University, who coauthored the study with Steven Webster. Most “independent” voters still lean toward the left or right, and their voting behavior reflects that tilt.

The social scientists analyzed decades of survey trends and found that as parties became more aligned with other cultural divisions like race and religion, voters on the left and right viewed each other more and more negatively. The division has driven a boom in “negative partisanship”—an increased tendency to vote consistently against one of the parties, even if one self-identifies as an independent.

Another factor in the rise of negativity, according to political psychologist Jon A. Krosnick of Stanford University, is that negative politicking taps into how humans process facts.

“One piece of negative information has more of a damaging effect than a piece of favorable information has a positive effect,” Krosnick says. “If I can only hold your attention for a few minutes, and I can either tell you how I helped an old lady cross the street or how my opponent kicked a cat, it makes more sense for me to tell you about the cat.”

Humans cling to negative facts more than positive ones, even outside of political contexts, Krosnick says. He suggests this inner-Debbie-Downer may be tied to fear. Hanging onto negative information might have helped humans’ evolutionary ancestors avoid danger and survive to reproduce.

But elections aren’t necessarily doomed to be slugfests, according to a paper to be published in June, also in Electoral Studies. A research team led by Todd Donovan of Western Washington University found that the way elections are set up can make a significant difference.

Most elections rely on a system that allows each voter to cast one, nontransferable vote for one candidate. For example, a single voter can vote for Donald Trump or John Kasich, but not both. Some American cities, however, have adopted an alternative system called "preferential voting" that allows each voter to divide his or her loyalties.

Preferential voting can take different forms. In one system, each voter receives a lump sum of points and allocates those points among candidates. A gung ho Kasich enthusiast might give all of his point to Kasich, but a more conflicted voter might allot 70 percent of her points to Kasich and 30 percent of her votes to Trump. In this way, voters can support multiple candidates, and the candidate with the most points wins the election.

Another system of preferential voting allows each voter to rank candidates as first choice, second choice, and so on. (The voter above would rank Kasich as first choice, and Trump as second choice.) If no candidate receives a majority of first-choice votes, then second-choice votes come into play, and if necessary, third-choice votes, until one of the candidates has enough votes to win. The Australian House of Representatives relies upon this method, as do about a dozen U.S. cities, including San Francisco, Minneapolis and Cambridge, Massachusetts.

For his study, Donovan focused on ranked choice voting. Donovan says cities that adopt ranked voting often do so to save money because the system allows instant runoffs. But when he compared mayoral races in cities with conventional voting to those with ranked voting, he found the ranking method had another benefit: less negativity.

“I was kind of surprised,” says Donovan. “The civility thing is a bonus that I didn’t expect to see so pronounced.”

In cities with plurality voting, more than half of the voters said candidates criticized one another. But in cities with ranked voting, only 25 percent of voters reported similar hostility between candidates.

“It’s not a zero-sum game, so you’re not as likely to attack your opponents,” Donovan explains. Of course, candidates want to be ranked as first choice by voters, but candidates may also need to win second or third place votes, which could come into play after the first round of ballot counting. In the example above, Trump may want to win over Kasich voters, but attacking Kasich too much could sabotage chances of winning second or third place votes from supporters committed to Kasich. If Trump were too hostile to Kasich, Kasich supporters would be much less likely to rank him as second-choice, perhaps casting their second-choice votes for Ted Cruz instead. If attacks have more potential to backfire, candidates seem less inclined to draw blood in scraps with one another.

The national electoral process is unlikely to change in one fell swoop, according to Donovan; doing so would require a Constitutional amendment. But states can individually choose to adopt alternative voting systems, as can party-run caucuses and primaries. That might allow candidates to emerge from elections without the stench of negative campaigns wafting behind them.

For now, however, the foot fungus endures.