The Frustrating Inadequacy of Antidepressants

Why Prozac and its ilk so often fail, and why the future of psychiatry might be psychedelics

In 1897, the French sociologist Émile Durkheim decided to study and compare the suicide rates of different religions. He found that Protestants were most likely to commit suicide, and Jews least likely. Durkheim chalked it up to the absence of clergy and confessions in Protestantism, which he believed promoted loneliness, as well as the religion’s do-it-yourself spirit. If you don’t manage to do it yourself, then, it might lead you to feel profoundly, irreparably bad.

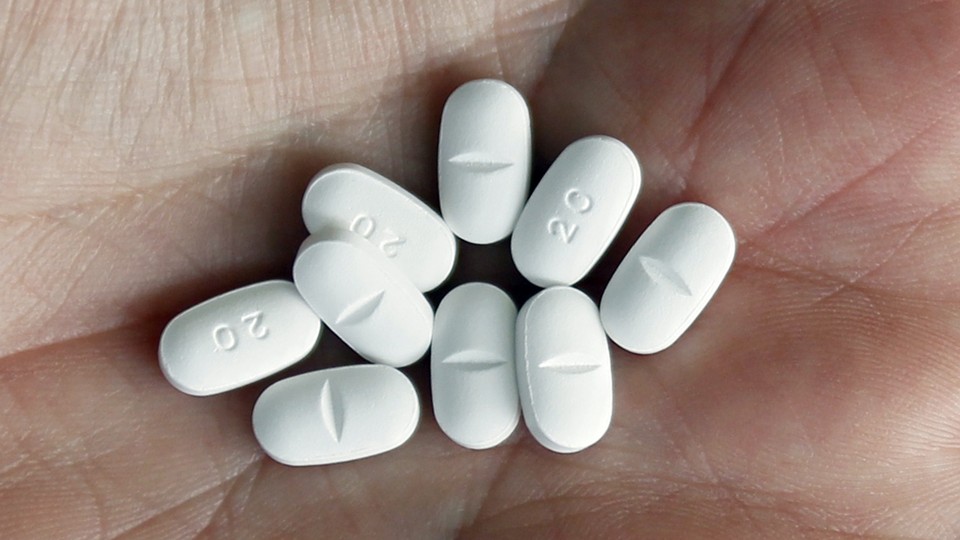

In her new book, Blue Dreams, Lauren Slater recalls Durkheim’s work to suggest that perhaps it’s partly because of America’s Protestant roots that our emotional wounds are so deep. Antidepressants are one of the most commonly prescribed drugs in the United States, but their side effects and trial-and-error nature often leave something to be desired. According to some studies, they are only about 50 percent more effective than placebo. Still, they are, for now, the best treatment we have for a disease that many people find crippling.

In her book, Slater, a psychologist and writer, explores the history of antidepressants, the science behind them, and the novel treatments that might soon replace them. I spoke with her recently about her research. An edited transcript of our conversation follows.

Olga Khazan: What were the options for depression before antidepressants came along?

Lauren Slater: You could be treated with morphine, which was legal for a long, long time. The use of the barbiturates became legal in 1904, and you could be treated with those. There were various tonics and brews that people made out of leaves. They would brew up teas. You could be treated with lithium. Lithium baths were pretty popular for a while.

Then the other thing was that you just didn’t treat it at all and you waited it out. Usually, depression remits, but sometimes it can take too long a time.

Khazan: Why was Prozac so different from the antidepressants that came before it?

Slater: The tricyclics, which came before Prozac, were thought only to be relevant for a population of very ill people, deeply depressed people, whereas Prozac was marketed right from the beginning to the general public. People used it to treat dysthymia, which is a more mild kind of depression. Prozac was like every man’s drug.

That said, when you look at the studies, there really is no difference in the efficacy rate of Prozac versus the tricyclics. The tricyclics worked on two-thirds of the people who try them. Prozac works on two-thirds of the people who try it.

Prozac was marketed as a site-specific drug. It was supposedly able to home in on a tiny target in the brain: It was a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, whereas the older drugs cast a wide net over the brain. But it’s almost preposterous to think that you can target just the serotonin system in the brain, because the serotonin system is linked to the dopamine system, which is linked to the norepinephrine system, which is linked to the other neurotransmitter systems.

Khazan: Why do antidepressants that work for people eventually stop working? You write about how that can be one of the most frustrating things.

Slater: No one really knows why that happens. It’s one of the risks you have to keep in mind when you decide to go off your drug; it might not work if you need to go back on it again.

Khazan: Why do Prozac and other selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors—or SSRIs—so often cause sexual side effects?

Slater: When you depress the dopamine function in the brain, then you get sexual side effects. You get a blunting of the libido. Prozac does that. It raises the amount of serotonin available, but it actually depresses dopamine.

Khazan: You write how there’s no consensus around the theory that depression is caused by a chemical imbalance. Why are these drugs so widely prescribed despite that? Why do we continue to put our faith in them?

Slater: First of all, they do work two-thirds of the time. We just don’t know how they work or why they work. Drugs like Prozac can almost miraculously clear away the clutter of mental illness. The other drugs that we have, the other SSRIs or other SSNRIs, they also work. That’s why we put our faith in them.

We also, in general, are told a tall tale by the pharmaceutical companies about the chemical-imbalance theory. That’s the tale we’re told when we’re given a drug. In diabetes, we know what’s happening. We know why blood sugar is high or can get very low. We don’t know, in the case of the SSRIs or the other antidepressants—we really don’t know what the etiology of the disorder is. [But] we’re told [by doctors and drug makers] that we do know.

Khazan: Why do you see psychedelics, such as psilocybin, as the future of psychiatry?

Slater: Because I don’t see any new drugs in the pipeline. There could be something someone’s at work on and it’s going to come through and it’s going to be completely different from anything you’ve ever seen before. I somehow don’t think so. I think that for the time being, we’re going to have selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Any new drugs that come in are going to be variations on that. Psychedelics, though, are truly novel drugs. They work completely differently. The beauty of them is you can take them just once or twice. You get a significant mind shift from that. That can be curative, especially for things like addiction, where you can take a psychedelic and realize on the psychedelic that you are ruining your life and the lives of those around you. You can have that kind of deep realization and then deep commitment to change, which can work.

That’s what you’re trying to do in psychotherapy. You’re trying to shift a person’s paradigm, or a person’s plot they have of their life. My life is terrible, I hate my job. My spouse and I are always arguing, my house is a mess. This is a story that a person tells themselves about their life. Psychedelics blow that story open and suddenly there’s room for a new narrative. I don’t see anything coming along that’s going to be quite as powerful as what those drugs have to offer.

Khazan: You write that you actually don’t want prescribing privileges, which some psychologists have advocated for. Why don’t you want that option?

Slater: There’s this sense that I have that I got from doing this book that psychiatry wasn’t going anywhere. The SSRIs were a big breakthrough. Those happened 30 years ago. Since then nothing of import has come to us.

I don’t want prescribing privileges because I don’t want to see psychiatry fail as a medical science. If psychologists get prescribing privileges, then pretty soon social workers are going to ask for prescribing privileges. Then licensed mental-health practitioners will be asking for prescribing privileges.

Pretty soon all sorts of people who don’t have medical degrees or medical training will be asking for prescribing privileges. The field will get farther and farther away from its original mission, which was to be a medical science. I’d like to see psychiatry succeed. Success would be that they’re able to come up with some theories that pan out as to what depression is or where depression is in the brain.